News Story

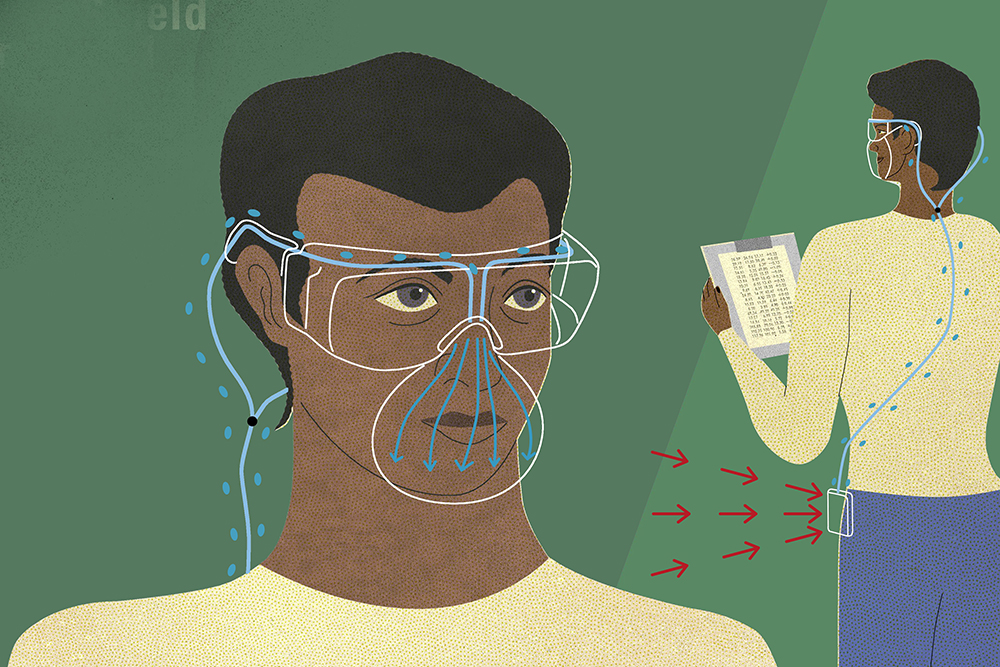

Studying Airborne Transmission of COVID-19

In February, Jelena Srebric was celebrating the release of a long-awaited study on the transmission rates of influenza in dorm rooms, research conducted as part of UMD’s C.A.T.C.H. the Virus study, when the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in the United States.

“When COVID-19 hit, we were in a good position because we had just completed the influenza study, so it was just a matter of mobilizing people quickly into this space,” says Srebric, acting associate dean for research and professor of mechanical engineering, who has been researching airborne viruses for more than 12 years.

At the Center for Sustainability in the Built Environment (CITY@UMD), Srebric and her colleagues, in collaboration with Professor Donald Milton and UMD’s School of Public Health, are employing multi-scale modeling and computational fluid mechanics to track particle emission and movement of the novel coronavirus in generic indoor spaces under a variety of real-world conditions: classrooms with open windows or reconfigured desks; school buses and airplane cabins; a two-hour class versus a 30-minute meeting.

“Using these simulations, we’re able to reliably see where those particles end up under very realistic environmental conditions,” she says. “That will be vital to moving us forward.”

This summer, they began offering initial results of these simulations online: simple animations to help visualize the trajectory of pathogen spray. In one study, the team found that infected students in the back of a school bus—far away from the circulating air—were less likely to spread the virus to nearby students, compared to those sitting closer to the front. Studying air flow in a typical classroom, they found that ventilation systems with intake and outtake vents in the ceiling are less effective at diluting COVID-19 particles than other systems.

“I think for many people, seeing is believing, so visualizing the data has been really important,” she says.

The research also sets the stage for next steps. While Srebric says good ventilation, fresh air, masking, and distancing help minimize spread, they are just placeholders for the massive infrastructure changes needed to manage airborne pathogen outbreaks. She points to technologies like ultraviolet irradiation as the next frontier. Currently being used in hospitals and even subway cars, the nearly centuries-old technology can obliterate pathogens quickly, particularly when paired with ceiling fans, which draw air and accompanying pathogens upward. Srebric and her colleagues are now coordinating a multi-university center to push an agenda for creating the next generation of devices and systems.

“The number of airborne pathogens like influenza, and now COVID-19, is unnecessary,” says Srebric. “And until pharmaceutical solutions are developed, you have a time gap where engineering solutions that are energy-efficient, easy-to-use, and scalable can really save lives.”

… And the Band Played On

As many high schools and universities return to campus this fall, one time-honored tradition is under scrutiny: is it safe for the marching band to perform in person? Working with researchers at the University of Colorado, Srebric and UMD colleagues are applying their research to help determine what sort of distance and interventions are needed and for how long band members can play together safely. This team is studying emission amount, velocity, and trajectory for a number of wind and brass instruments and singers under a variety of conditions. The studies will hopefully provide best practices for band directors with regards to practice spaces (e.g., arranging chairs and grouping instruments). The work is sponsored by the National Federation of State High School Associations and College Band Directors National Association, who fundraised for the research among their own membership.

As many high schools and universities return to campus this fall, one time-honored tradition is under scrutiny: is it safe for the marching band to perform in person? Working with researchers at the University of Colorado, Srebric and UMD colleagues are applying their research to help determine what sort of distance and interventions are needed and for how long band members can play together safely. This team is studying emission amount, velocity, and trajectory for a number of wind and brass instruments and singers under a variety of conditions. The studies will hopefully provide best practices for band directors with regards to practice spaces (e.g., arranging chairs and grouping instruments). The work is sponsored by the National Federation of State High School Associations and College Band Directors National Association, who fundraised for the research among their own membership.

“It’s such a great cause,” says Srebric. “And a world without live music is no good!”

Published September 1, 2020