News Story

Blown Away

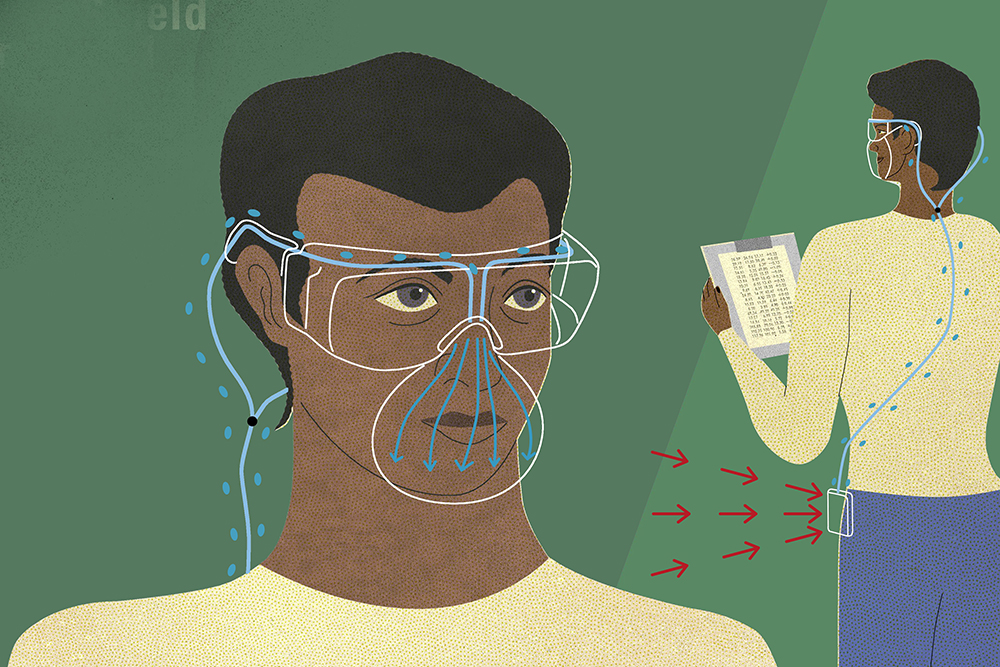

Opera students Christian Simmons M.M. ’21 (left) and Öznur Tülüoğlu M.M. ’21 rehearse masked and at a distance. Below, Ally Happ ’23 plays her French horn through a mask with a slit and with a bell cover over the instrument. At bottom, Neil Brown ’09, M.M. ’14, a trumpeter, has relied on his work as an audio engineer and teacher during the pandemic. (Photos by Stephanie S. Cordle)

The novel coronavirus had already begun its awful spread through the U.S. when on the evening of March 10, the singers of Washington state’s Skagit Valley Chorale gathered for rehearsal. For two and a half hours, with most group members less than six feet from one another, they raised their voices and filled the air with song—and, it turned out, something more sinister.

By the end of the month, 53 of the 61 attendees had fallen ill and two had died, making headlines nationwide. Amateur and professional performers and audiences suddenly faced an existential question: Just how dangerous is singing or playing instruments communally?

As communities around the nation continue to try to stave off the spread of COVID-19 with varying degrees of shutdown, that question has persisted, leaving in-person music, theater and dance performances mostly silenced. The creative industry lost 2.7 million jobs and more than $150 billion from April 1-July 31 alone, according to a Brookings Institution study.

The performing arts landscape remains murky until an anticipated vaccine is widely available, and for musicians, singers and other performers without institutional support, the pandemic has been a calamity: emotionally, socially and financially.

Jelena Srebric, a University of Maryland professor of mechanical engineering, has stepped onto this dark but brightening stage, co-leading a national study investigating how effectively the virus can be transmitted from the lips of a contralto or the bell of a trumpet to neighboring musicians or singers—and how to mitigate the risks.

At the same time, the university’s School of Music and School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies are pioneering creative ways to keep students learning and playing together even while distanced, thanks to new technology and teaching approaches, as well as outdoor opera, livestreamed plays, video projections and other innovations.

“I understand performers needing some presence of each other, because … they literally cannot perform (otherwise),” says Srebric. “I would do everything I physically can to help musicians (perform) safely because I understand the need.”

Music comes from deep inside us in the most literal sense, making it a moist, spitty business.

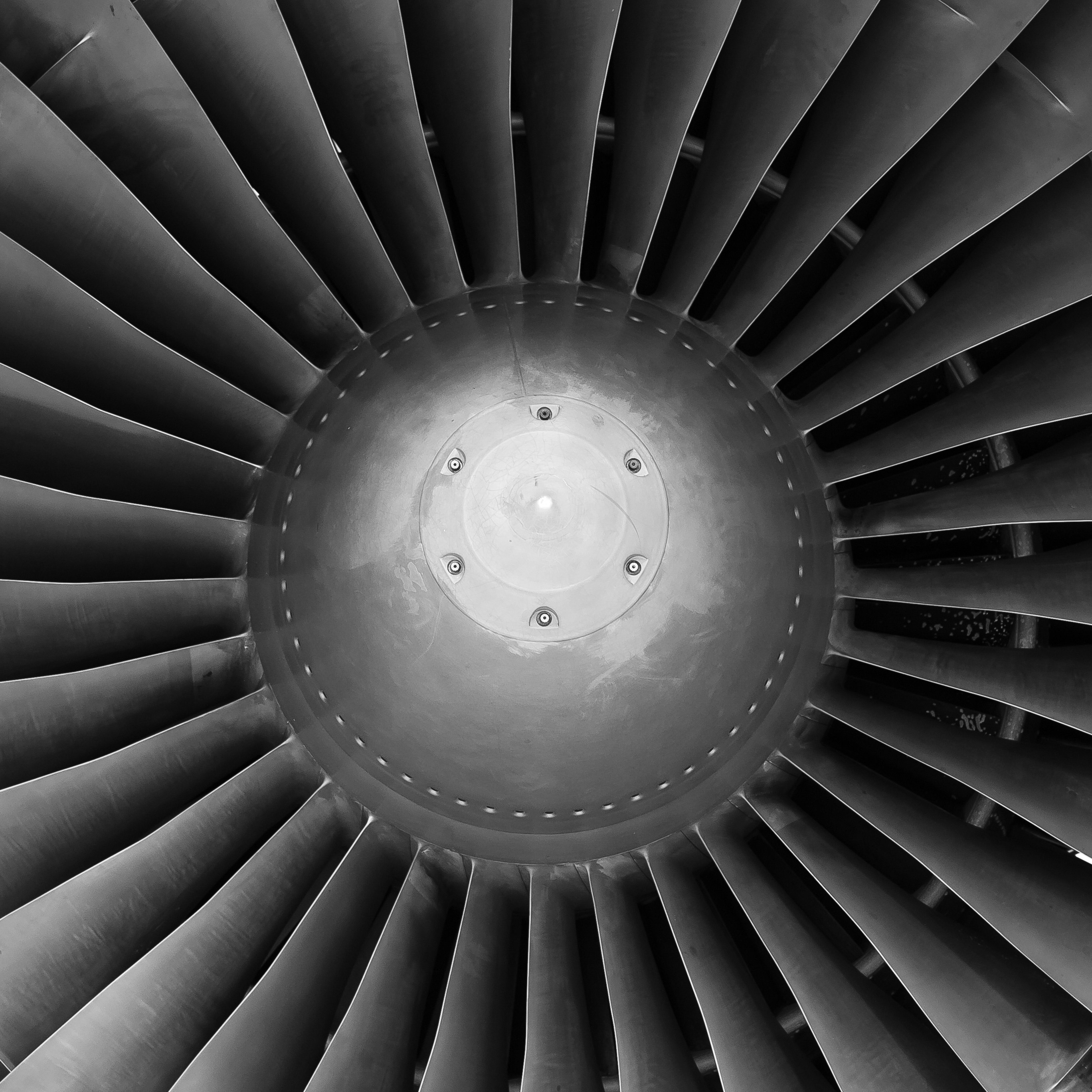

Whenever brass and woodwind instrumentalists play a scale or vocalists sing an aria, they expel bits of fluid into the air. Larger ones, known as droplets, fall to the ground within a few feet. But tiny ones, less than five micrometers in diameter, are known as aerosols. They linger in the air, travel farther than droplets and can persist on a surface for up to several hours.

Spooked by the Washington state choir disaster, Mark Spede, professor of music at Clemson University and president of the College Band Directors National Association, and James Weaver, director of performing arts and sports for the National Federation of High School State Associations, began diving into research on aerosol production in music performance, but found scant data. They convened a coalition of more than 125 arts organizations to pool resources and commission a study on COVID-19, singing and instruments.

The team quickly brought on Shelly Miller, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder, as a lead investigator to examine the aerosol projection and velocity of wind instruments, vocalists and actors. Soon, Srebric, who had long worked on indoor air quality and ventilation, and had published papers with Dr. Don Milton, professor of environmental health at UMD and influenza expert, joined, too.

At Colorado, Miller and her team enlisted instrumentalists to perform in front of lasers and stage fog, which allowed them to compute and visualize aerosol volume and velocity through clean air. The initial findings were a dismaying shock. “When (the Colorado team) showed us how much aerosol was coming out of the instruments, our hearts sank very quickly,” says Spede.

In College Park, Srebric and her team of students, using a high-speed camera, measured the particles in breath and speed of exhalation. Then they modeled how aerosols could disperse through recital halls or rehearsal spaces of various sizes, factoring in information about ventilation systems.

The team found that some instruments posed more of a threat than others. Trumpets and clarinets—instruments with a relatively simple, unimpeded shape from mouthpiece to bell—had higher concentrations of particles than more curved ones. It also determined that while most musicians should position themselves six feet apart, trombonists needed nine; they have to work harder to push sound to the other end of the elongated instrument, making them more efficient vectors—plus, with the slide fully extended, the trombone easily eats into those six feet.

Actors, too, produced many more particles while projecting their voices than typical conversation would, the findings showed. Researchers saw essentially no difference in the number of particles produced by playing an instrument, singing or speaking for the stage.

The results showed that performing or practicing outdoors, along with masks—both on the musician’s face if possible, with a small slit cut out for the player’s mouth, and a bell cover for wind and brass instruments—cut the risk of diffusing aerosols significantly.

“Huge,” Srebric says of the difference masks make. “You’re looking at a 50 to 70, 80% reduction in the concentration of particles and the velocity.”

Even outside, Srebric recommends that musicians or singers move to a new location or take a five-minute break after an hour of practice. “You build up the concentration” in the air, she says. Moving to a different area or pausing to allow wind to shift the air reduces the aerosols present, she says.

After the initial guidelines were released in July, Srebric received a deluge of questions from music teachers and band leaders around the country who were hungry for information. What type of fabric should we use for masks (Surgical masks are good, and more important than fabric is fit: Make sure they’re snug around nose and chin. For instruments, a scrap of pantyhose stretched around the bell works.) How long can we stay in a rehearsal space (Thirty minutes, maximum.) How can musicians empty spit valves safely? (Easy—use a disposable puppy pad.)

Lynne Gackle, national president of the American Choral Directors Association and professor of ensembles and director of choral activities at Baylor University in Texas, says Miller’s and Srebric’s work has “definitely informed everything we are doing at our university right now.” In the fall, her student singers wore masks, met in a large church sanctuary with a good ventilation system and went outside every half-hour to let the air clear.

For Gackle, the guidance allowed a return to the splendor of live music. “On Sept. 7, when I sat in front of that choir and they began to sing, it moved me emotionally,” she says. “I looked out and they were moved emotionally, and I saw tears. I get chills thinking about it right now.”

Still, Srebric is bearish on the return of music as leisure until a vaccine is widely available. For musicians, “playing music together is a pretty social experience,” she says. Attending a concert for pleasure, she believes, constitutes “an unnecessary risk.”

The specifics of breath control, the technicalities of finger placement—can those be taught over video conferencing? Last spring, faculty and staff at UMD who focus on musical performance faced unique challenges as classes pivoted quickly to virtual instruction. Justin Drew M.M.’07, D.M.A. ’19, a lecturer in French horn performance in the School of Music (SOM), says that his was the “ability to discern information in real time—hearing someone play and then instructing the student on how to move forward.”

As students followed directions to record their performances on cell phones or laptops, and to use video conferencing to communicate with their instructors, lag time, distortion and generally poor audio quality made the nuances of playing nearly imperceptible. Playing in ensembles over video was all but impossible.

The School of Music’s leadership matched funds from a UMD teaching innovation grant and found a solution for the Fall 2020 semester: high-quality web cameras and recorders, as well as software, for the more than 400 music majors. The Zoom Q2n-4K “has been such a game-changer,” says Drew. The camera/recorder provides an audio recording much better than those available on computers or phones. “I’m able to discern a lot of nuances and details in (students’) playing,” he says. “It’s really changed the experience for both students and me, as a teacher.”

SOM also provided mic stands, tripods and other equipment to students—who now own the items. “You don’t know how many 500 mic stands are until you get a truckload of mic stands,” says William Evans, lecturer and director of the music technology lab, who coordinated the purchase of the equipment and its distribution. (Students who couldn’t come to the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center in person received their devices by mail.)

New ways of creating music, art, theater and dance have been key to continued teaching and learning within SOM and UMD’s School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies (TDPS). Last spring, undergraduates acted in a live virtual production of the fantasy show “She Kills Monsters,” which The New York Times said “made particularly impressive use of filters;” the paper also noted the livestream had twice as many viewers as a simultaneous YouTube reading of playwright David Mamet’s “November,” which featured John Malkovich and Patti LuPone.

For some, the move online has expanded the options for guest instruction. Through The Clarice’s Artist Partner Programs, percussion and jazz students have attended a virtual clinic with Boston-based Grammy-winning drummer Terri Lyne Carrington. TDPS students took a hip-hop class with the London theater and dance collective Far From the Norm.

The outdoors has been essential: Craig Kier, associate professor and director of the Maryland Opera Studio, led opera students in socially distanced rehearsals in the courtyard of The Clarice. During Homecoming week in October, Alexandra Kelly Colburn ’18 directed “art is water, seeds are change,” a video installation of short films projected onto one of The Clarice’s exterior walls.

“There’s no question that none of us want to see this continue much longer,” says Gregory Miller, SOM director and horn professor. “But I don’t think the students are learning any less because of the situation—it’s just a different kind of learning.”

Still, technology can only go so far in replicating the thrill of creating music with others. For many, the loss is palpable and painful—both in terms of income lost and the energy created by and exchanged between artists engaged in the joint pursuit of something transcendent.

“The ensemble experience is really important to learn how to play with others,” says Ally Happ ’23, who plays the French horn. “It’s where people get joy from being in music.”

When Heather MacArthur ’14, M.M. ’17 learned that the Colorado Springs Philharmonic, in which she plays violin, was canceling its spring season, she didn’t immediately worry. Instead, she traveled around the country, learning songs about whatever state she happened to be in and performing them in pop-up concerts for passersby: “Meet Me in St. Louis” at the Gateway Arch, “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the U.S. Capitol.

Trumpet player Neil Brown ’09, M.M. ’14 had just returned in early March from touring Texas and Louisiana with one of his groups, the sweetly named Peacherine Ragtime Society Orchestra, when its trips to Ohio and Pennsylvania were suddenly canceled. He had hoped to play some gigs on Easter—a big day for trumpeters—but “it became increasingly clear this was here to stay for a while,” he says.

Working as a recording engineer and teacher has helped Brown stay afloat, and others have adjusted to a new, roomier, airier reality. MacArthur played a weekly, outdoor summer concert series in Colorado, where, over several acres, local bands and musicians performed with lots of space between them and the audience. With the Fort Collins Symphony Orchestra, she played in an indoor performance, with all musicians masked and the wind players surrounded by Plexiglas; only 50 spectators were allowed in the vast hall.

Some performers are using the pandemic as inspiration for their art. Gabriel Mata-Ortega M.F.A. ’21 has altered his disco-based dance thesis so that his movement is constrained to an 8 x 8-foot square. “I want this space to be seen as a limitation, but also (ask): What can it afford or provide? What space am I making, and how is it helping me?”

Srebric’s research continues, deepening the understanding of aerosol spread. Her team recruited singer Allison Hughes for an experiment led by doctoral student Lingzhe Wang that took place in the lab’s environmental chamber, a temperature-controlled room with highly purified air that makes the accumulation of particles, their source and their movement clearer. Tracking velocity and particle concentration as Hughes sang, Wang and the team found that a box fan fitted with an air filter reduced particle concentration by about half, and wearing a mask while singing provided near-perfect prevention of aerosol spread

Srebric hopes that her work will provide a template for a life in which, gradually, in-person harmonies and melodies will reach us all again, even if COVID remains with us for some time. “Without music,” she says, the world “is a really sad place.”

This story first appeared in Maryland Today.

Published February 4, 2021