News Story

Improve the Outcome: Vascular Liver Tissue

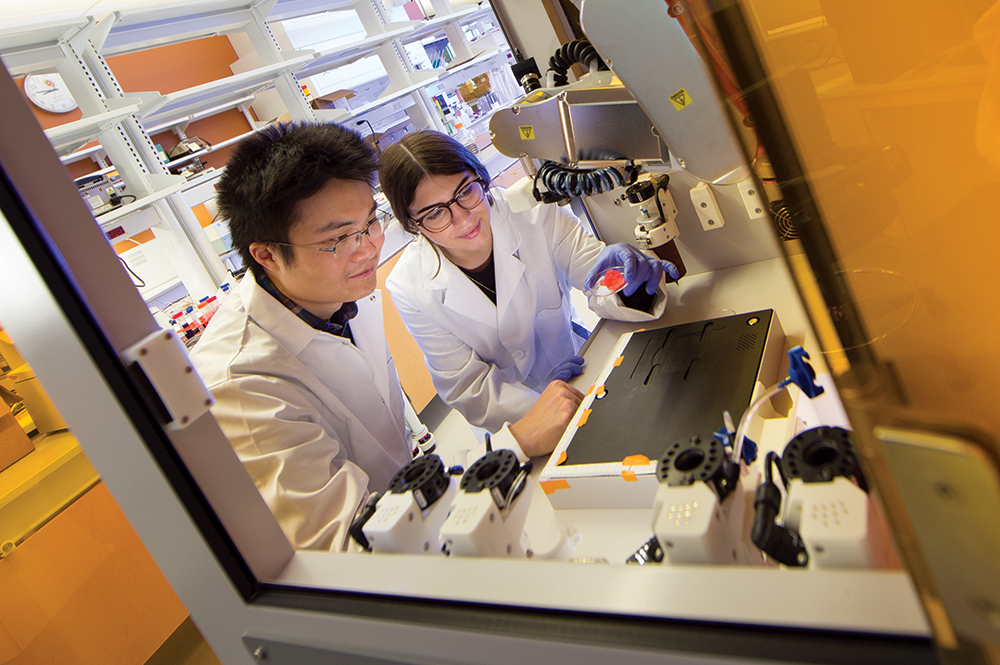

Guang Yang (left) and Julia Pinsky holding lab-grown engineered tissue. Photo: John T. Consoli

There are 4.5 million adults living in the U.S. with liver disease; roughly 41,000 of them will die from it each year. As is true for many patients whose organs succumb to disease or injury, those in the late stages of liver disease have limited options. Two years ago, NASA and the New Organ Research Alliance announced a competition aimed to kick-start possible advancements in creating vascular organ tissue in a lab, a discovery that could open new doors to drug testing, disease modelling, and organ transplants. The ask was steep, but so was the reward: produce metabolically functional human vascularized organ tissue more than a centimeter thick that can live for 30 days, and win a share of $500,000.

Developing something as complex, time-consuming, and intricate as lab-raised vascularized tissue requires heavy investment, but the NASA challenge was unlike any typical research project underway in A. James Clark Hall.

“It’s a different approach to science,” says John Fisher, chair of the Fischell Department of Bioengineering. “Typically, research projects are topically driven. We put together a proposal for something we want to study further, send it to an agency, and—if they think there’s merit—they give us funding. In this case, NASA outlined very specific criteria and said, ‘if you do this, we'll reward your efforts.’”

Fisher’s lab had previously made some progress in perfused tissue, so the potential for success was there—but the funding was not. And then the Mpact Challenge was announced.

“Previous studies we had done in the lab suggested a possible strategy and we felt like we had a solid approach, but we couldn’t have pursued it without Mpact,” says Fisher.

With so much at stake, it might surprise some to know that Fisher’s lab largely tapped undergraduates—some with little to no lab experience—to noodle the NASA challenge. It’s the undergrads, according to Assistant Research Professor Guang Yang, that can bring the infectious enthusiasm and fresh perspective to push a project to the next level.

“It’s the undergrads that can bring the infectious enthusiasm and fresh perspective to push a project to the next level.”

“This lab has a long tradition of contributing to the training of undergraduate students who are interested in doing this type of benchwork research,” says Yang. “They start from scratch, but it doesn’t take long to move them from trainees to productive colleagues.”

Undergraduate Julia Pinsky, who was one of two undergraduates working on the project last fall, says the experience has opened her eyes to life in the lab, giving her unparalleled hands-on and instructional learning experiences. It was also a sobering look at the patience, effort, and time required in research. It’s these hard and soft skills that Yang strives to provide every student who works with him.

“My goal is for students to gain three sets of skills by the time they finish their degree,” he says. “Obviously we want them to garner the experiment skills they’ll need for a future career, but I also want them to know how to deal with setbacks and understand what it takes to pull off a research project. The shiny eye-catching data is only the tip of the iceberg; being hands-on allows you to know the bulky part underneath the water.”

As far as the actual project is concerned, Fisher says they are close; he expects they’ll have something to show NASA this spring. As for his student researchers, they’re already a success.

“I feel strongly that, among the various roles we play, a significant one is that we are exposing and teaching students about research so that if it appeals to them, they can think about it as a potential career,” says Fisher.

“Just being in this lab has opened a lot of doors for me,” says Pinsky. “I feel really fortunate that Drs. Fisher and Yang took me on. I’m still learning; it’s been such a great opportunity to try these things.”

Read more about the Mpact Challenge projects.

Published March 15, 2020