‘I Still Consider Myself Undocumented’

From Mexico to College Park, Professor Finds His Path and Tries to Lead Others to Academic Excellence

By Liam Farrell

Main photo by Tony Richards; graduation and family photos courtesy of Osvaldo Gutierrez

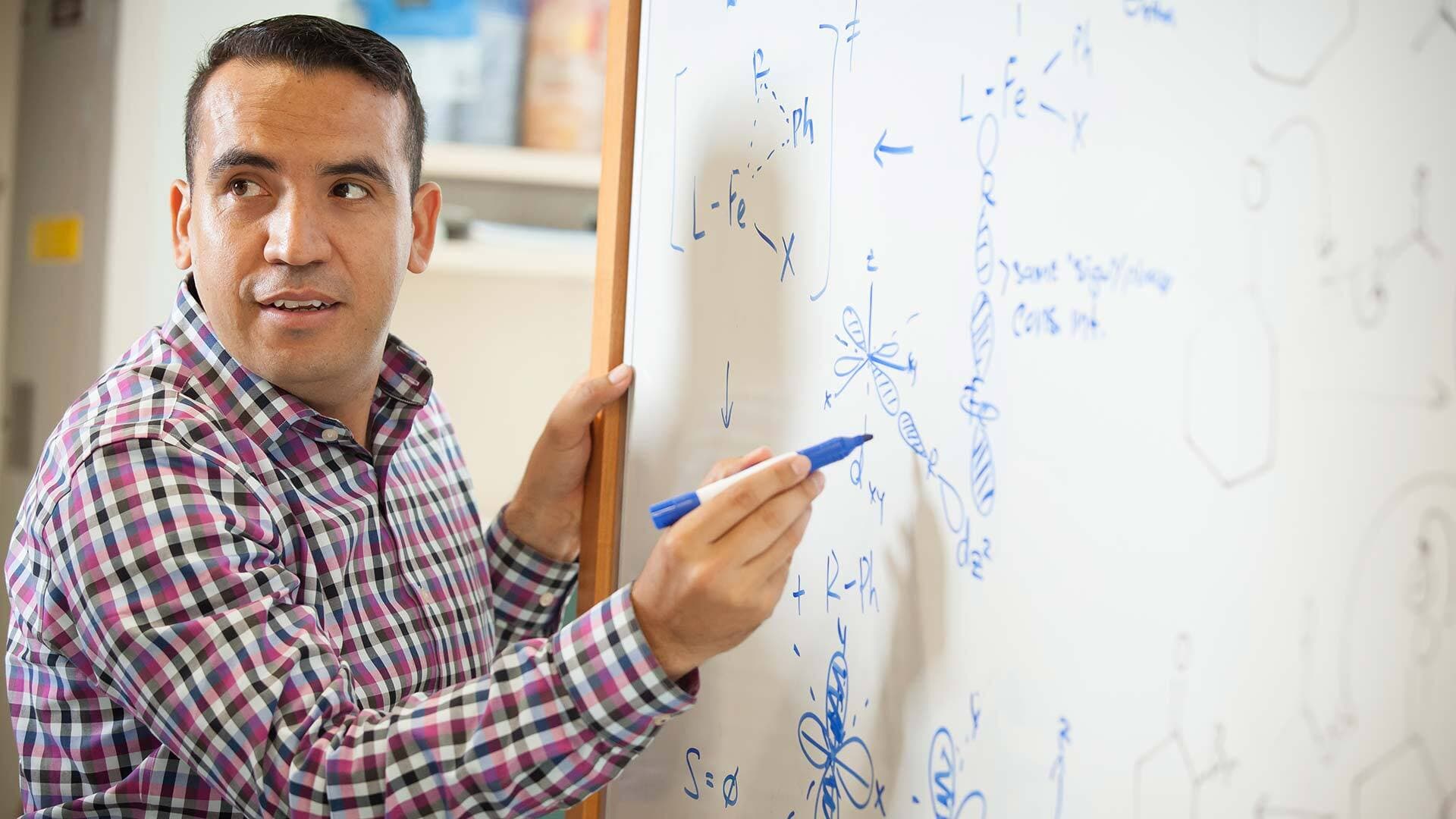

A formerly undocumented immigrant, chemistry Assistant Professor Osvaldo Gutierrez has dedicated himself to making medicine more accessible and building a pipeline for underrepresented populations into the sciences. Below, Gutierrez stands with his parents, Soledad and Miguel Gutierrez, at his doctoral graduation ceremony at UC Davis. At bottom, after years of struggle in the immigration system, Gutierrez, pictured with his wife and daughters, became a U.S. citizen in January.

Before a 9-year-old Osvaldo Gutierrez began the more than 1,600-mile migration from Mexico to California with his father and five of his siblings in 1993, he made a promise to his grandfather to not return until he became a doctor.

Growing up in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato, Gutierrez had spent more time tending goats than finishing schoolwork. Nobody in his family—encompassing 11 children at the time, and eventually 14—had gone to high school, let alone college. The decision to head north let his ambition free, and he did become a doctor, albeit of another kind.

Today he’s an assistant professor at the University of Maryland and a rising experimental chemist researching new computational and experimental methods to create cheaper, more effective medicines. Gutierrez, whose life was often unsteady due to the shifting sands of U.S. immigration rules over the past 25 years, also feels a responsibility to help other people on the margins get a chance to join academia.

“I always needed that person to speak up. Now I think I need to do a bit more,” he said. “I still consider myself undocumented. I feel that kind of responsibility.”

A hard journey

The border between the United States and Mexico was more porous in Gutierrez’s youth, and his grandfather had taken part in the Bracero Program that brought millions of Mexican laborers into America on temporary contracts.

As Mexico’s economy teetered in the early 1990s, other members of Gutierrez’s family started crossing the border for work as well. Gutierrez remembers many long walks at night across the open desert before eventually being loaded into the trunk of a car and getting out only when it parked in Santa Ana, Calif.

The family fully reunited in Sacramento, where Gutierrez’s father mowed lawns and did cleaning and maintenance for apartments. In a two-bedroom house, seven girls shared one room while seven boys slept in the living room; a few cousins staying in the garage provided extra income.

Hostility toward immigrants was reaching a fever pitch in that era of Proposition 187, an eventually scuttled law approved by California voters in 1994 to deny undocumented immigrants access to state services and public education. Kids at school or in his neighborhood taunted Gutierrez with racist insults and terrifying threats to call the police on him or his family.

“You definitely felt that you were not welcome,” he said.

Surrounded by drugs and violence, all of Gutierrez’s siblings eventually dropped out of high school, and after a guidance counselor told him his immigration status would seriously hinder his ability to apply for college and get financial aid, his 3.9 GPA dropped to a 1.8. Most of his energy was reserved for working in a bakery from 4 p.m. to 2:30 a.m.

His outlook changed, however, with the passage of the California Dream Act, allowing undocumented immigrants meeting certain criteria to be treated like other state residents in higher education. Gutierrez enrolled at Sacramento City College, eventually earning his B.S. and M.S. from the University of California, Los Angeles.

“It became clear that he was something special,” said Kendall Houk, the Saul Winstein Distinguished Research Chair in Organic Chemistry at UCLA and a mentor for Gutierrez.

Legal and financial uncertainty still dogged Gutierrez, however. He kept to himself, rarely asking for help or describing his personal life in detail; he would sleep in labs and avoid any situation involving showing identification.

“My family thought I had kind of made it, but I was still washing dishes,” he said. “You were living a really day-by-day sort of thing.”

His dream of becoming a doctor ran aground with medical school applications asking for a Social Security number, because without one he would only be considered for admission, scholarship and financial aid purposes under more stringent international student guidelines. But at that point he had discovered a love of research and teaching with Houk, who helped connect him to a Ph.D. program at UC Davis.

His dream of becoming a doctor ran aground with medical school applications asking for a Social Security number, because without one he would only be considered for admission, scholarship and financial aid purposes under more stringent international student guidelines. But at that point he had discovered a love of research and teaching with Houk, who helped connect him to a Ph.D. program at UC Davis.

By the time he earned his doctorate in 2012 and began a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania, the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program had started giving renewable two-year reprieves from deportation and eligibility for work permits to undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children.

“It was a blessing,” he said.

Focusing on the “little” things

Relief is the dominant emotion that Gutierrez feels since becoming a U.S. citizen in January.

“I can focus now on the small things,” he said.

“Small things,” of course is a relative term. Since coming to UMD in 2016, Gutierrez has been trying to revolutionize the methods to glue molecular components that chemists use in making medicines. While the most effective versions of these typically involve expensive metals like palladium, Gutierrez is trying to substitute much cheaper iron instead.

His innovative methods led to his securing a $1.9 million research award from the National Institutes of Health and being named to the American Chemical Society’s Talented 12. Rather than undertaking expensive, real-world trial and error, Gutierrez first uses computer modeling to give him insight into chemical reactions before undertaking traditional experiments, one of the few researchers in the country employing such a strategy.

It’s work that took on added importance after his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. Before she died in Fall 2016, Gutierrez said, her quality of life was significantly boosted by medicines that gave her the energy to do things everyone takes for granted, from talking with family to getting her own glass of water.

It’s work that took on added importance after his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. Before she died in Fall 2016, Gutierrez said, her quality of life was significantly boosted by medicines that gave her the energy to do things everyone takes for granted, from talking with family to getting her own glass of water.

“It just gave my research a different feeling, how those compounds were changing her life,” he said. “We can make people’s lives better.”

A board member with the Alliance for Diversity in Science and Engineering, Gutierrez also runs a summer internship program that so far has brought seven minority community college students to his lab. Chris Acha ’22, who spent six weeks with Gutierrez in 2017 as a Prince George’s Community College student, is now studying for a degree in chemical engineering at UMD and said the experience was a turning point.

“It’s hard to find people who even look like you in the engineering department,” Acha said. “He gave me a reason to continue.”

Gutierrez thinks if he had been aware as a child of the impact he can have now—in the lab, as a mentor and traveling around the country sharing his research and life story—he would have made a different one.

“If I knew the life of a professor (then),” he said, “I would have promised my grandfather to be a professor.”