Getting the Checkerspot out of Checkmate

Photo Illustration by Kelsey Marotta

Photo Illustration by Kelsey Marotta

Let’s just get this out of the way: We all agree the Monarch butterfly is a great butterfly, richly colored, majestic in size, etc. Practically everyone knows and loves Monarch butterflies.

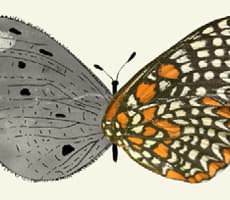

But how many other kinds of butterflies can average Marylanders name? If the Monarch is truly it, then meet Euphydryas phaeton. It’s similarly colored, with a slightly more complex—and some might say more distinguished—pattern of black, orange-gold and white. True, with a wingspan of about 2.5 inches it lacks the Monarch’s kite-like dimensions. Bigger doesn’t always mean better, does it?

Most importantly, the butterfly commonly known as the Baltimore checkerspot is our butterfly. It’s the state insect of Maryland, reportedly named in honor of George Calvert, First Lord Baltimore, because its wings are reminiscent of the Maryland founder’s coat of arms.

And it needs our help, says a group of students, faculty and staff who’ve started a crowdfunding campaign through May 8 at Launch UMD to help bolster the once-common species’ faltering numbers.

“It used to be in 15 counties in Maryland, but now it’s only found in seven,” says entomology student Meghan McConnell M.S. ’17, a member of PollinaTerps, a campus group dedicated to supporting pollinator insect species. “And they’re only in a few places now. All the colonies that are natural, rather then restored, are found right along the Pennsylvania border.”

So what led to the decline of the Baltimore checkerspot in places like College Park, where it was common when it became state insect in 1973?

The main factor, says postgraduate insect researcher Nathalie Steinhauer Ph.D. ’17, is believed to be the decline of wetlands and marshes, home of a plant that Baltimore checkerspots feed on exclusively as young caterpillars—the white turtlehead (How Maryland is that?!). Later they drop to the ground and live under leaf litter through the winter in preparation for their emergence as butterflies the following summer.

Without enough of the plants, colonies of butterflies can’t sustain themselves. And then, as biologists say, they become extirpated—locally extinct. Today, the butterfly is classified as imperiled in Maryland.

Without enough of the plants, colonies of butterflies can’t sustain themselves. And then, as biologists say, they become extirpated—locally extinct. Today, the butterfly is classified as imperiled in Maryland.

Deer, which are common on campus and throughout the state, don’t make things any easier, she says.

“It’s the result of habitat loss and construction and urbanization, and the deer can make it really hard to bring turtlehead plants back because they like eating them,” she says.

Other reintroduction efforts have failed because not enough habitat in the form of white turtleheads was provided for butterflies being set free in the wild, says Carin Celebuski, head of the PollinaTerps group and coordinator of volunteers at the University of Maryland Arboretum.

UMD’s reintroduction effort will be different, she said. In late May, volunteers hope to begin planting young turtleheads in wet places around campus, such as the area near the UM-Shuttle bus facility off Paint Branch Drive. The several plantings will be enclosed with deer-resistant fencing or surrounded with smelly plants deer don’t like.

“We are focused this year on making sure we have the habitat that the butterflies need,” Celebuski says. “We want to have a thriving self-sustaining community on campus, both of Baltimore checkerspots and turtleheads.”

If the plantings take hold, next year could see the introduction of captive-bred butterflies to the new habitat. The group will be working closely with MDNR on data keeping and monitoring of variables both to help ensure success and to guide future reintroduction efforts for the butterfly.

“They definitely want this to be science-based, not DIY,” Celebuski says.

If successful, it would be the second colony to be reintroduced in Maryland, joining another at Black Hill Regional Park in Montgomery County.

Like other butterflies, Baltimore checkerspots play an important role in pollination of plants and the overall health of the ecosystem that supports not only them, but us, says entomology Professor Dennis vanEnglesdorp, who’s known for his work with honey bees.

“This is exciting—it’s breaking new ground for us,” he says. “Sort of like the panda is the symbol of wildlife protection for the World Wildlife Fund, I can see this becoming a symbol on a smaller scale here on campus of what we can do for a species at risk.”